Part

numbers and technical information

Understanding Spitfire part Numbers.

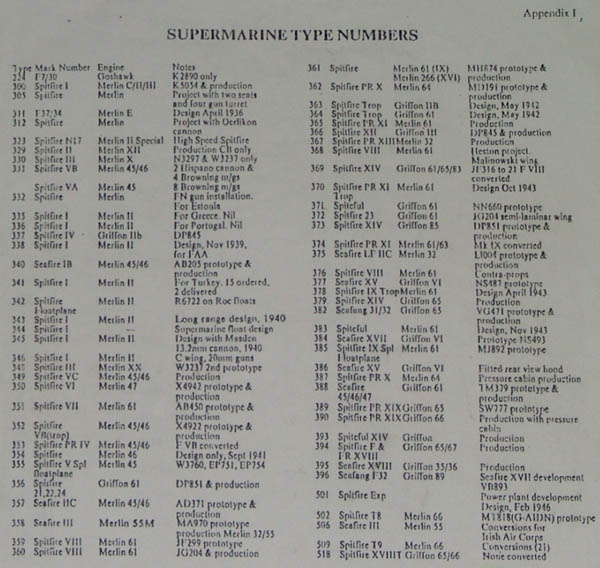

Spitfire part numbers

are 7 digit numbers always starting with 3. The first 3 digits tells you the Mk

of aircraft 1e

300 =Mk 1

The

first three numbers only changed if

the part was modified.

Therefore you still get 300 part numbers

on later Marks of Spitfire, the first three digits will only tell you which mark

of aircraft the part was first fitted to.

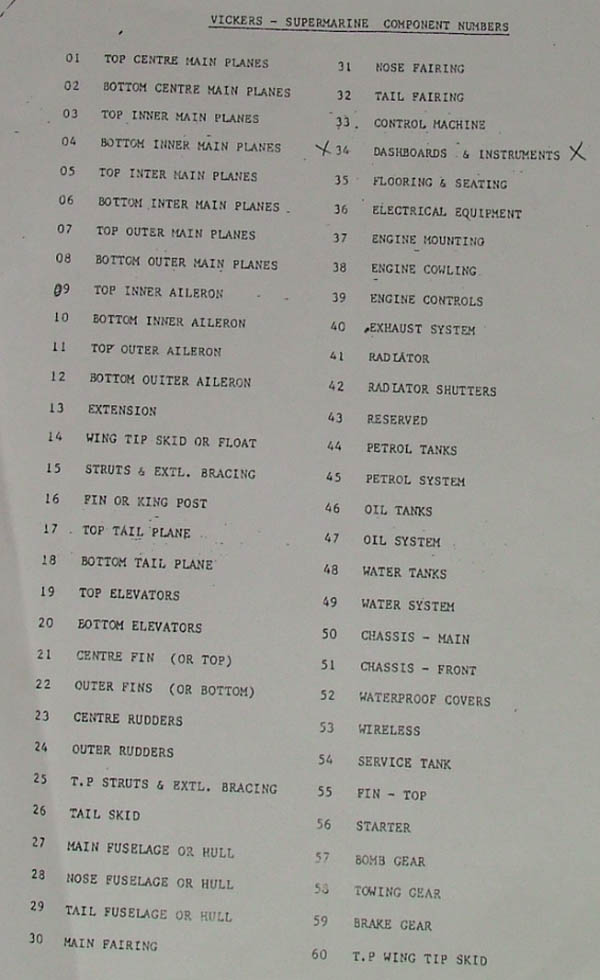

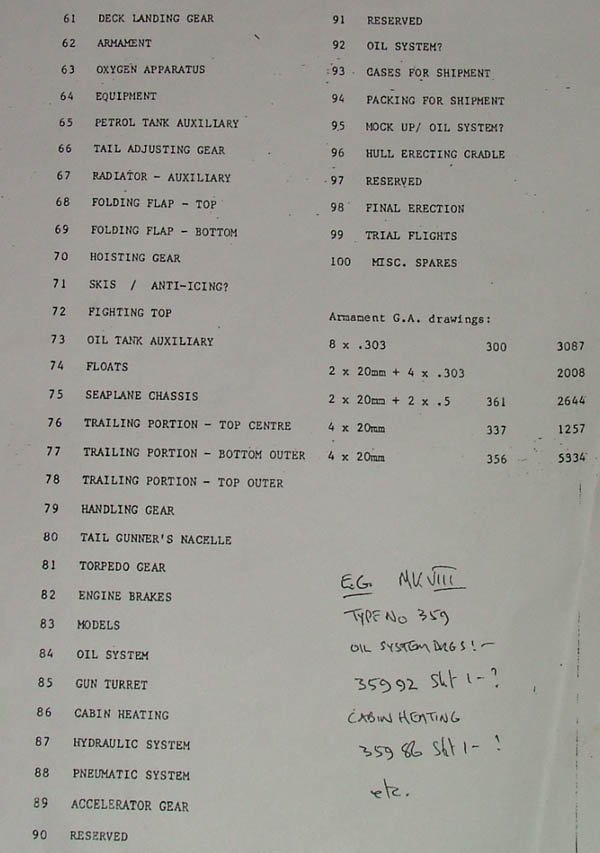

The second set of digits relates to the type of part

or location of the part in the aircraft this will become clear when you study

the pictured lists of numbers to follow.

The last 2 digits are the actual part number, relating to that

individual part.

This only applies to Spitfire parts.

The numbering system to other British built aircraft are different.

It is important to understand that the Spitfire along with every other

Wartime aircraft is also made up of generic parts such as instruments which

could be fitted to other types of aircraft , these do not

carry the 300 numbers.

Therefore the golden rule is this,

only parts which have a number starting with 3 followed by two other digits is

specifically made for the Spitfire. So next time you see a part advertised as

Spitfire look for the part number. This is not to say a particular part was not

fitted to the Spitfire it just means it is not specifically Spitfire and could

also be fitted to another aircraft type.

Just to

confuse you there are a few instruments that are Spitfire only such as the trim

gauge, fuel gauge and the undercarriage indicator but these will carry the 300

number.

Example 300 45 **

300 = Mk1 Spitfire

45 =Petrol Tanks

**= Individual part

number

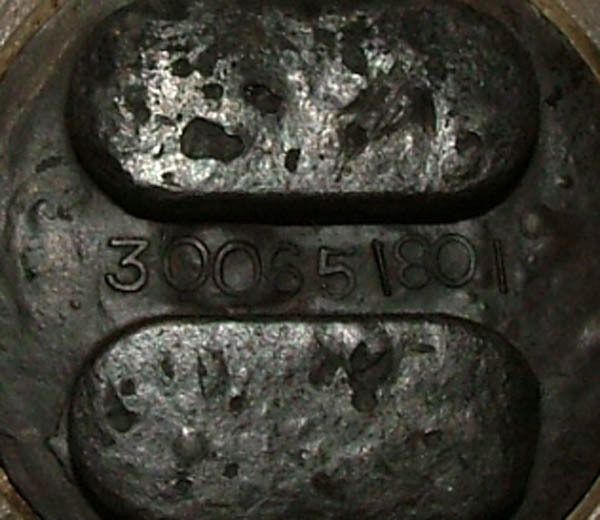

This is a

part I recovered from a disused airfield at Culmhead . I found lots of these parts and did not have a clue what they

were until one day I found one with a bung in it and the magic Spitfire number.

3006580

According to the parts

list its a Mk1 part i.e. 300 , however as previously stated it could be fitted to any

following Mk of Spitfire if this part

was not modified.

The 65 means it was petrol tank auxiliary.

80 is the part

number.

This turned

out to be a drop tank part.

This would tie in nicely with Culmhead as allot of Spitfires operated with drop tanks from this field.

On

D-Day Seafires fitted with drop tanks escorted Typhoons on ground attack

missions.

Unlike the

Germans whose parts are easy to identify as their part numbering system was

logical and standard across all aircraft types the British system is

chaotic and each manufacturer used their own system.

The following numbers lists relating to all kinds

of components for all kinds of aircraft it is only with experience that you will

learn to understand the various part numbering systems and identify unknown

parts but at least the following numbers give you a fighting chance..

Some numbers are repeated in the lists but all

contain useful information.

Airframe codes

Chipmunk T MK 10

26AF Hurricane including Tempest spares

26AJ Spitfire & Seafire

26AL Sunderland 5

26AN Oxford 1 & 2

26AQ Sea Hawk

26AT Wellington B10 T10 & 18

26BA Halifax

26BJ Martinet 1

26BM Attacker F & B

26BN Proctor 3 & 4

26BP Beaufighter TT10

26BT Barracuda 3

26BU Gannet AS1 & T2

26BV Sycamore HR

26BW Dominie 1

26BX Typhoon including Tempest spares

26BY Mosquito & Sea Mosquito

26BZ Firefly

26DA Javelin F (AW)

26DB Whirlwind & Westland Sikorsky S55

26DC Vulcan B

26DD Anson

26DE Victor B1

26DF Beverley C

26DG Seamew

26DH Scimitar F1

26DJ Belvedere HC

26DK Lightening

26DL Comet 2

26DM Britannia

26DN Gnat Trainer

26DP Alouette (British spares)

26DQ Basset CC1

26DR Beaver AL

26DV Venom FB NF & Sea Venom FAW

26EA Lancaster , Lincoln 2 & York C1

26ED Horsa 2

26EH Meteor F8 & T7

26EM Sea Otter

26EN Auster

26ER Tempest 2, TT5 & 6

26ET Meteor NF & TT20

26EV Vickers 1000 Transport Aircraft

26EW Hornet & Sea Hornet

26FA Brigand

26FC Vampire & Sea Vampire

26FH Sea Fury

26FK Hastings

26FL Valetta & Viking

26FM Prentice T1

26FN Devon C

26FP Shackleton

26FR Winged Targets

26FU Balliol & Sea Balliol

26FV Dragonfly HC & HR

26FW Heron

26FX Hunter & De Havilland N139D(Type 110)

26FY Sea Vixen

26FZ Canberra

26GA Bristol standard parts for Beaufighter, Brigand & Buckmaster

26KK Osprey

26LK Hercules CMK1

26MM SA330E Anglo-French Helicopter

26NA Buccaneer

26NB Belfast

26PH Phantom GRF

26PJ Jet Provost T

26PN Percival Provost T1

26PP Pembroke HC, C1 & Sea Prince

26RA Jaguar

26SA Pioneer CC1

26SH Sea King

26SK Skeeter

26SR Valiant B

26SS Swift

26SW Scout [& Wasp]

26TA Andover

26TD Dominie T

26TP Twin Pioneer

26TT Tiger Moth 2

26TV Varsity T1

26UU Wellington 1

26V Hart DB & India & T

26VA Harrier GR

26VC VC10C

26WA Argosy

26WX Wessex

26A - Swordfish

26AAA - Hector

26AC - Blenheim

26AH - Botha

26AK - Henley

26ALS - Tucano airframe

26AM - Hampden

26AR - Botha

26AS - Mentor and Magister

26AU - Lysander

26AV - Lerwick

26AW - Bombay

26AX - Manchester/Lancaster

26AY - Beaufort

26AZ - Defiant

26BE - Fulmar

26BF - Stirling

26BG - Harvard

26BH - Hudson

26BK - Albermarle

26BL - Whirlwind(fighter)

26BQ - Queen Wasp

26BS - B45 Tornado

26BV(1) - Vega Gull & Q6

26BW - Dominie and Rapide

26C - Ripon

26CB - Sioux

26CC - Hinaidi II

26CCC - Gladiator

26C* - Impressed aircraft

26CJ - F86 Sabre

26CP - Moth Minor

26D - Iris

26DD(1) - Dart

26DS - TSR2

26DY - Venom

26E - Fury

26EA - Lancaster/Lincoln

26EC - Warwick

26EE - Sedburgh

26EF - Hengist

26EG - Welkin

26EJ - Welkin

26EL - Firebrand

26EQ - Eton

26EX - Messenger

26EY - Kirby Cadet and Grasshopper

26EZ - Buckingham and Buckmaster

26F - Vimy

26FD - Spiteful

26FE - Prefect Glider

26FF(1) - Grebe

26FF(2) - Marathon

26FJ - Sturgeon

26FS - Wyvern

26FT - Athena

26G - Wapiti

26GG - Rangoon

26GRP - GRP Glider, Janus, ASW19, ASW21

26HH - Tomtit

26J - Whitley

26JJ - Battle

26JU - Expeditor

26K - Bulldog(Bristol)

26L - Nimrod(Hawker)

26LE - Gazelle

26LX - Lynx

26M - Cloud

26MA - Tornado GR1/F3

26MH - Vigilant

26MR - Jetstream

26N - Southampton

26NN - Gauntlet

26NS - Bulldog T1

26P - Audax

26PL - Hawk

26PN - Percival

26PP(1) - Avro 504K

26PP(2) - Test Benches

26PPA - Phantom Potential Assets

26Q - Tutor(Avro)

26QF - BAe airframe spares

26QQ(1) - Gauntlet

26QQ(2) - Gannet

26R - Sidestrand

26RDK - Lightning

26RM - Non-RAF Tornado common items(repairable)

26RP - Phantom recce pod

26RSH - Sea King airframe

26S - Vildebeast

26SG - swallow

26SP - Puma

26SS - Victoria(1)

26T - Hyderabad and Hinaidi

26TC - Tucano

26TS - Tristar

26TT(2) - to 26AE

26VB - Harrier GR5/7/10

26VN - Sea Harrier

26VV - Horsley

26W - Demon

26WW - Siskin

26Y - Flycatcher and Harrow

26YY - Gordon and Seal/A1F

26Z - Virginia

26ZZ - Atlas

Codes (US Spares)

Ref. Airframe

CK Chinook

HA Baltimore

HF Boston

HG Buffalo

HH Bermuda

HJ Vigilant

HK Catalina

HL Liberator

HO Lightening

HP Maryland

HT Vengence

HU Goose

JH Lodestar

JJ Argus

JL Mitchell

JM Marauder

JP Mariner

JQ Dakota

JU Expeditor

JV Coronado

JZ Hadrian

KB Ventura

KC Piper Club

KG Cornell

KN Expeditor (US)

KL Hoverfly

'36' Codes Engine Spares

Ref. Engine

Bombardier 20801

36AC Olympus

36AD Viper

36AE Conway

36AF Rover airborne aux power plant

36AH Proteus

36AK Orpheus

36AL Alvis Leonides

36BB Artouste Patouste & Turmo

36BC Nimbus

36DD Rolls Royce Merlin and tools

36DE Gnome

36DG Gyron Junior

36DT Dart

36FF Gypsy Major & Gypsy Queen & De Havilland tools

36HH Rolls Royce Griffon and tools

36HS Hawker Siddeley fuel control equipment

36JJ Derwent turbine engines

36KK Goblin 2 & 3

36LL Lucas fuel equipment

36M Sabre and Napier repair tools

36MM Dowty fuel system equipment

36NG Gazelle

36PG Pegasus

36PP Python 2 & 3 engine

36Q Rolls Royce Nene jet

36R Bristol Mercury, Centaurus & Hercules tools

36SN Rolls Royce Spey Mk201/202

36SS Sapphire

36ST Rolls Royce Spey Mk250

36SY Rolls Royce Spey

36TN Rolls Royce Tyne

36TT Ghost

36TU Rolls Royce Turmo III

36U Cheetah & Armstrong Siddeley tools

36VV Rolls Royce Avon jet

36W Centaurus & Bristol tools

36WW Double Mamba

Electrical Equipment

Lighting and Miscellaneous Equipment

5B Aircraft Wiring Assemblies

5CW Aircraft Electrical Switches, Switchboxes, Relays and Accessory

Items

5CX Aircraft Electrical Lamps, Indicators, Lampholders and Accessory

Items

5CY Aircraft Electrical Plugs, Sockets, Circuit Markers, Suppressors and

Accumulator

Cut-outs

5CZ Aircraft Electrical Miscellaneous Stores

5D Aircraft Armament Electrical Stores

5E Cable and Wire Electrical Stores

5F Insulating Materials Electrical Stores

5G Special Ground Equipment

5H Standard Wiring System

5J Batteries Primary and Secondary

5K Electrical A.G.S and Bonding Stores

5L Electric Lamps

5P Ground Charging, Transforming Equipment and Motors

5Q Ammeters, Micro-ammeters, Milli-ammeters, Voltmeters and Milli-voltmeters

5S Strip Wiring Components

5UA Aircraft Engine and Air Driven Electrical Current Producing

Equipment and Spares

5UB Aircraft Electrically Driven Electrical Current Producing and

Transforming Equipment

and Spares

5UC Aircraft Electrical Current Control Equipment and Spares

5UD Aircraft Electrical Motors, Blowers and Spares

5UE Aircraft Electrically Driven Pumps, Accessories and Spares

5V Aircraft Electrical Domestic Equipment

5W Aircraft Electrical Actuators, Accessories and Spares

5X Component Parts of Wiring Assemblies

Radio, Radar, Telephone and Telegraphic Equipment

Miscellaneous Radio (Wireless) Equipment

10AB Miscellaneous Radio (Radar) Equipment

10AC Unassembled Items peculiar to Radio with Generic Headings similar

to those in Sections

28 and 29

10AD Items and Assemblies performing Circuit Functions (Nomenclature

commencing Letters

A-K)

10AD Items and Assemblies performing Circuit Functions (Nomenclature

commencing Letters

L-Z)

10AF Calculating, Indicating and Measuring Equipment

10AG Tools and Tool Boxes peculiar to Radio

10AH Telephone Head Equipment, Microphones and Receivers

10AJ Mountings and their Component Parts

10AK Dials, Handles, Knobs, Plates, Escutcheon, Pointers, Press buttons

and Scales

10AL Screens and Insulating Components and their Assemblies

10AM Labels (Radio)

10AP Boxes, Cases, Covers and Trays, other Cases, Transit

10AQ Furniture, Tentage, textile Materials and Ventilator Equipment,

peculiar to Radio

10AR Machinery, Machine and Mechanical Parts other than those in Section

10AC

(Nomenclature commencing Letters A-K)

10AR Machinery, Machine and Mechanical Parts other than those in Section

10AC

(Nomenclature commencing Letters L-Z)

10AT Windows and Visors

10AU Strip Metallic

10B Radio (Wireless and Radar) Aerial and Mast Equipment and Insulators

10BB Radio (Radar) Aerial and Mast Equipment and Insulators

10C radio Chokes, Capacitors and Inductors (see also Joint-Service

Catalogue)

10CV Joint Service Common Valves

10D Radio (Wireless and Radar) Equipment, Modulators, Panels, Receivers,

Transmitters etc.

10DB Radio (Radar) Equipment, panels, Power Units, Racks, Receivers and

Transmitters

10E Magnets and Radio Valves (Industrial Types)

10F Radio (Wireless and Radar) Starters and Switch Gear

10FB Radio (radar) starters and Switch Gear

10G Ground Telephone and Telegraph Equipment

10GP Ground Telephone and Telegraph Equipment - Post Office Pattern

10H Radio Connectors, Discs Indicating, Fuses, Leads, Plugs and Sockets

and Ancillary

Parts,

Holders and Terminals.

10HA Radio (Wireless and Radar) Connectors, Cords Instrument and Leads

10J Radio Remote Controls

10K Radio (Wireless and Radar) Power Units and Transformers

10KB Radio (Radar) Power Units and Transformers

10L Radio (Wireless and Radar) Control Units

10LB Radio (Radar) Control Units

10P Radio (Wireless and Radar) Filter and Receiver Units

10PB Radio (Radar) Filter and Receiver Units

10Q Radio (Wireless and Radar) Indicating Units

10QB Radio (Radar) Indicating Units

10R Radio (Wireless and Radar) Transmitter Units

10RB Radio (Radar) Transmitter Units

10S Radio (Wireless and Radar) Test Equipment

10SB Radio (Radar) Test Equipment

10T Radio Monitors and Wavemeters

10U Radio (Wireless and Radar) Amplifying Units, Loudspeakers and Sound

Reproduction

Equipment

10UB Radio (Radar) Amplifying Units and Loudspeakers

10V Radio (Wireless and Radar) Oscillator Units

10VB Radio (Radar) Oscillator Units

10W Radio Resistors and miscellaneous Spares

10X Radio Crystal Units

10Y Cases Transit (general Radio purposes)

General Ground and Air Armament Equipment

and Torpedo Sights

9A Aircraft Towed Target Gear

9B Armament Ground Instructional Equipment

11A Aircraft Bomb Gear

11C Rocket Projector Gear

40H Gun Turret Cases and Airtight Containers

50A Aircraft Gun Turrets

50CC Boulton Paul Gun Turret and Gun Mounting Tools

50DD Bristol Gun Turret Tools

50EE Frazer Nash Gun Turret Tools

50H Aircraft Gun Turret Maintenance Equipment

50J Free Gun Mountings

Instruments, Models, Navigation and Plotting Equipment, Aircraft

Automatic Pilots

Aircraft Engine and Flying Instruments, Accessories and Spares

6B Aircraft Navigation Equipment, Accessories and Spares

6C Instrument Test Equipment, Tools, Accessories and Unit Equipment

Spares

6D Aircraft Gaseous Apparatus and Ancillary Equipment

6E Miscellaneous Instruments, Accessories and Unit Servicing Spares

6H Aircraft Automatic Pilots, Marks 4 and 8, Major Components, Servicing

Spares and Tools

6J Aircraft Automatic Pilots, Types A3 and A3A and A.L.1, Major

Components, Servicing

Spares and Tools

6S Automatic Stabilisers, Major Components, Servicing Spares and Tools

6T Aircraft Automatic Pilots, Marks 9, 10, 10A, 13, SEP 2, 14 and 17,

Major Components,

Servicing Spares and Tools

6W Instrumemnt Ancillaries to Radio Equipment

6Z Radio activity Detection Equipment and Accessories, Unit and Major

Servicing Spares

13 Drawing Instruments

52 Recognition Models

54A Plotting Equipment

Photographic Equipment

Cameras

14B Photographic Processing Equipment, Enlargers and Accessories

14C Projection, Assessing Apparatus and Epidiascopes

14H Photographic Test Apparatus

General Aircraft Equipment

Aircraft Personnel Equipment

15A Man-carrying Parachutes

15C Equipment-dropping and Sea-rescue Apparatus

15D Air Sea Rescue and Equipment, and Supply-dropping Parachutes

25A Propellers

25B Aircraft Radiators

25D Spinners for Fixed Pitch Propellers and Fairey Spares for Metal

Propellers

27A Aircraft Wheel Equipment

27B Aircraft Air and Oil Filters, Fuel and Oil Coolers

27D Miscellaneous Aircraft Cover Equipment

27F Aircraft Pumps and fuelling Equipment (Airborne)

27G Aircraft Brake System Equipment

27H Miscellaneous Aircraft Equipment

27J Aircraft Control Handles with Gun, Camera, R.P. and Brake Operating

Mechanisms

27K Teleflex Aircraft Remote Control Equipment

27KA Exactor Aircraft Remote Control Equipment

27KB Aircraft Controls - Roller Chains

27KD Pressurised Cabin Equipment - Normalair

27M Aircraft Hydraulic and Undercarriage Equipment - Lockheed

27N Airborne Fire Fighting Equipment

27R B.L.G. Oleo Leg Equipment

27S Standard Ball and Roller Bearings other than M.T.

27T Controllable Gills

27U Airborne Heaters

27UA Aircraft Cabin Cooling Equipment

27V Aircraft Controls - Teddington

27VA Aircraft Controls - Dunlop

27VC Aircraft Controls - Palmers

27W Aircraft Hydraulic and Undercarriage Equipment, Standard Design

27WW Aircraft Windscreen Wiper Equipment

27Z Turner Duplex Hand Pumps for Aircraft Hydraulic Systems

27ZA Exactor Self Sealing Couplings

A.G.S. and General Hardware

A.G.S.

28E Clips A.G.S.

28F Couplings A.G.S.

28FP Aircraft Fastener and Quick Release Pins

28G Eyebolts A.G.S.

28H Ferrules A.G.S.

28J Filler Caps and Fuel Filters A.G.S.

28K Fork Joints A.G.S.

28L Locknuts, Lockwashers A.G.S.

28M Nuts A.G.S.

28N A.G.S. Miscellaneous A to O

28P Pins A.G.S.

28Q Rivets A.G.S.

28R A.G.S. Miscellaneous P to R

28S Screws A.G.S. Miscellaneous A to O

28T Studs A.G.S.

28U Trunnions and Turnbuckles A.G.S.

28V Unions A.G.S.

28W Washers A.G.S.

28X Wire A.G.S.

28Y A.G.S. Miscellaneous S to Z

29A Bolts and Nuts, General Hardware

29B Screws, General Hardware

29C Eyelets, Roves, Screw Cups, Washers, General Hardware

29E Pins, Woodruff Keys, General Hardware

29F Rivets, General Hardware

Workshop, Ground, Hangar, Marine and Compressed Gas Equipment

Workshop Equipment

4C Airfield Equipment

4F Air Compressors and Servicing Trolleys

4G Aircraft Servicing and Ground handling Equipment

4K General Ground Equipment (including Refuelling Equipment)

4N Sparking Plug Testing and Servicing Equipment

4FZ Air Compressor Spares

71B Plants (Mobile, Transportable and Static) and Plant Accessories

Manufacturer

Codes/inspectors stamps.

Inspection stamps are

usually small circles containing text or numbers they were applied to

say the part had past inspection and can identify the factory or

manufacturer

AS = Airspeed

AW = Armstrong Whitworth

R3 = Avro

BP = Boulton Paul (possibly EP)

FB = Bristol

DH = de Havilland

DHB - de Havilland, Broughton

DHC - de Havilland, Christchurch

DHL - de Havilland, Lostock (usually propellers)

EEP = English Electric Preston

F8 = Fairey Engineering

GAL = General Aircraft Limited

G5 = Gloster

HA = Hawker – also 41H?

HP = Handley Page

MCO = Morris Cowley Oxford

PAC = Percival Aircraft Corporation

PPA = Miles (Phillips & Powis)

R = Republic

SB = Short Brothers

SFR = Rootes Speke

SR = Saunders Roe

SHB = Short & Harland Belfast

SHR = Short & Harland Rochester

TAY = Taylorcraft

VA = Victory Aircraft

VACB = Vickers Armstrong Castle Bromwich

VACH = Vickers Armstrong Chester

VABL = Vickers Armstrong Blackpool

WA = Westland

Miscellaneous Codes:

AGS = Aircraft General Standard (Often on nuts and bolt heads)

ALCLAD = Aluminium (Or “Alooominum” if from former colonies!)

ALCOA = Aluminium Corporation of America

PSC = Pressed Steel Company

Manufacturer Codes/inspectors stamps:

AS = Airspeed

AW = Armstrong Whitworth

BP = Boulton Paul (possibly EP)

C = Canadair (inspector's id number is arranged vertically within the C)

(Sabre Mk.4 & Mk.6)

CAA = Commonwealth

Aircraft

CCF = Canadian Car & Foundary (Hurricane Mk.IIB and Mk.IIC)

CH = Claudel Hobson

DH = de Havilland

DHB = de Havilland, Broughton

DHC = de Havilland, Christchurch

DHL = de Havilland, Lostock (usually propellers)

EEP = English Electric Preston

FB = Bristol

F8 = Fairey Engineering

FL = Folland

FM = Fairey

GAL = General Aircraft Limited

G5 = Gloster

GHCH = George Hardman Ltd. of Haywood Lancs

HA = Hawker – also 41H?

HP = Handley Page

HPL = High Speed Plastics Ltd. of Bangor, N.Wales

LAP = London Aircraft Production

Group (Halifax)

LBSB = Austin Motors Longbridge

LTAF = London Aircraft Production

Group (Halifax)

MCO = Morris Cowley Oxford

N = Noorduyn (UC-64 and Harvard)

PAC = Percival Aircraft

Corporation

PP = Miles

PPA = Miles (Phillips & Powis)

R = Republic

R2 = Rootes Secturities (Blenheim, Beaufighter and Halifax)

R3 = Avro

RR = Rolls Royce

RY = Avro (Yeadon)

SB = Short Brothers

SFR = Rootes Speke

SR = Saunders Roe

SHB = Short & Harland Belfast

SHR = Short & Harland Rochester

TAM = Tampier (Bloctube Controls Ltd. of Aylesbury)

TAY = Taylorcraft

VA = Victory Aircraft

VACB = Vickers Armstrong Castle Bromwich

VACH = Vickers Armstrong Chester

VABL = Vickers Armstrong Blackpool

WA = Westland

Aircraft Part Codes:

P39 = Airacobra (Bell)

AW41 = Albermarle Mk1

652A = Anson (All Mk’s)

660 = Argosy

UC61 = Argus Mk1 (Fairchild)

UC61A= Argus Mk II

UC61K= Argus Mk III

55, 56 = AT-6

77, 78 = AT-6A

84 = AT-6B

88 = AT-6C

121 = AT-6D

168 = AT-6G

804 = AT-11

54576 = AT-17

701 = Avro Athena T2

540 = Avro 504K

582 = Avro 504N

187 = Baltimore (Martin)

PD = Battle

PC = Battle

PA = Battle

156 = Beaufighter Mk1F

152 = Beaufort

126 = Beaufort DAP

192 = Belvedere (Westland)

B101 = Beverley (Blackburn) C1

555 = Bison

142M = Blenheim Mk IF

149 = Blenheim Mk Ib

160 = Blenheim Mk V

130A = Bombay

12 or 13 = Boomerang (CAC)

B26 = Botha

164 = Brigand

F2A = Bristol Fighter

19 = BT-9

19A = BT-9A

23 = BT-9B

29 = BT-9C

63, 74, 79 = BT-13

B103 = Buccaneer

B339E = Brewster Buffalo

105A = Bristol Bulldog Mk II & IIa

EA3 = Canberra B2

EA2 = Canberra PR3

EA4 = Canberra Mk24

SC4 = Canberra U/D 10

28 = Catalina Mk I

CH47 = Chinook HC1

C1 = Chipmunk T10

60 = Cirrus Moth Mk I & II

106 = Comet Mk I – IV

20 = Commando

C47 = Dakota Mk I

C53 = Dakota Mk II

C47A = Dakota Mk III

C47B = Dakota Mk IV

P82 = Defiant

104 = Devon

89A = Dominie Mk I

‘(B = Dominie Mk II

AS10 = Envoy Mk III

229 = Fortress Mk I

60M = Gipsy Moth

HP57 = Halifax Mk I

HP59 = Halifax Mk II

HP61 = Halifax Mk III

HP63 = Halifax Mk IV

HP63 = Halifax Mk V

HP70 = Halifax Mk VIII

HP71 = Halifax Mk IX

HP52 = Hampden Mk I

HP54 = Harrow

16 = Harvard I

66 = Harvard II

88 = Harvard IIa

AT16 = Harvard IIb

HP67 = Hastings

HP94 = Hastings C4

DB7 = Havoc I

DB7A = Havoc Mk II

75 = Hawk (Curtis)

P1182 = Hawk (BAe)

C130K = Hercules (Lockheed)

14 = Heron

HP50 = Heyford

103 = Hornet

87 = Hornet Moth

AS51 = Horsa (Also marked AS58)

16 = Hudson

L-214 = Hudson Mk I

L-414 = Hudson Mk II-VI

P1067 = Hunter Mk I

P1099 = Hunter Mk6

P1101 = Hunter T7

TypeS = Jaguar

TypeM = Jaguar T2

121 = Jaguar

GA5 = Javelin

145 = Jet Provost

87 = Kittyhawk (P-40)

683 = Lancaster (All Mks)

691 = Lancastrian

32 = Liberator

22 = Lightning (P-38)

P1B = Lightning Mk IF

P25 = Lightning Mk 2F

P26 = Lightning Mk 3F

P11 = Lightning T4

P27 = Lightning T5

694 = Lincoln

P8 = Lysander

M14 = Magister Mk I

679 = Manchester

179 = Marauder

M25 = Martinet TT1

M9 = Master Mk I

M19 = Master Mk II

M27 = Master Mk III

M16 = Mentor

G41A = Meteor Mk I

G41F = Meteor F4

G43 = Meteor T7

G41K = Meteor F8

G41L = Meteor FR9

G41M = Meteor PR10

NA62B = Mitchell Mk I

NA82 = Mitchell II

NA-108 = Mitchell III

98 = Mosquito (All Mks)

73 = Mustang I (Also NA83)

91 = Mustang Ia

97 = A-36 Apache (with dive brakes)

99 = P-51A / Mustang II

102 = Mustang III

103 = P-51C (early version) / Mustang III

104 = P-51B (later version) / Mustang III

106 = Mustang

109 = Mustang IV

111 = P-51C (later version) / Mustang III

111 = P-51K-NT (early Dallas-built = Mustang IVA

122 = P-51D-NA (later version) / Mustang IV

124 = P-51D-NT (late version Dallas built) / Mustang IV

26 = Neptune

HS801 = Nimrod (BAe)

AS10 = Oxford MkI & II

AS46 = Oxford MkV

P66 = Pembroke

F-4 = Phantom

P28 = Proctor I

P30 = Proctor II

P34 = Proctor III

P31 = Proctor IV

82B = Queen Bee (Pilotless?)

C1-13 = Sabre (F-86)

696 = Shackleton

382 = Spiteful

300 = Spitfire Mk I; Ia; Ib

329 = Spitfire Mk IIa & IIb

375 = Spitfire Mk IIc

353 = Spitfire Mk IV

332 = Spitfire Mk Vb

331 = Spitfire Mk Vb

349 = Spitfire Mk Vc & LF Vb

352 = Spitfire F Vb

351 = Spitfire Mk VII

359 = Spitfire Mk III

361 = Spitfire Mk IX

362 & 387 = Spitfire Mk X

365 = Spitfire Mk XI

366 = Spitfire Mk XII & XIII

367 & 353 = Spitfire Mk XIII

369 & 379 = Spitfire Mk XIV & XIVe

380 = Spitfire Mk XVI

394 = Spitfire Mk XVIII

389 & 390 = Spitfire Mk XIX

356 = Spitfire Mk F21; F22 & F24

SB29 = Stirling

S25 = Sunderland

541 = Swift (Shorts)

546 = Swift (Supermarine)

171 = Sycamore HA12

82 = Tiger Moth

81A-1 = Tomahawk Mk I

81A-2 = Tomahawk Mk II

621 = Tutor (Avro)

89 & 93 = Thunderbolt

637 = Valetta

706 & 710 = Valiant

100 = Vampire Mk F1; F3; F5; F9

113 = Vampire NF10

115 = Vampire T11

668 = Varsity

112 = Venom

V146 = Ventura

237 = Ventura Mk V

HP80 = Victor

498 = Viking C2

FB27 = Vimy Mk IV

698 = Vulcan

03 = Wackett (CAC)

236 = Walrus

462 = Warwick ASR Mk I

413 & 611 = Warwick II

460 = Warwick III

474 & 475 = Warwick V

485 = Warwick ASR Mk VI

345 = Washington B1

P14 = Welkin

287 = Wellesley

285 & 290 = Wellington I

408 & 409 = Wellington Ia

415 & 450 = Wellington Ic

298 & 406 = Wellington II

417 & 440 = Wellington III

410 & 424 = Wellington IV

407 & 421 = Wellington V

442 & 449 = Wellington VI

429 = Wellington VIII

440 = Wellington X

454 & 458 = Wellington XI

455 = Wellington XII

466 = Wellington XIII

467 = Wellington XIV

P9 = Whirlwind

AW = Whitley

SP = Whitley

01 or 02 = Wirraway (CAC)

244 = Wildebeeste I

258 = Wildebeeste II

267 = Wildebeeste III

286 = Wildebeeste IV

685 = York C1

Air Ministry Equipment Codes:

5A = Ground Lighting and Miscellaneous Equipment

5B = Aircraft Wiring Assemblies

5CW = Aircraft Electrical Switches, Switchboxes, Relays and Accessory

Items

5CX = Aircraft Electrical Lamps, Indicators, Lampholders and Accessory

Items

5CY = Aircraft Electrical Plugs, Sockets, Circuit Markers, Suppressors

and Accumulator Cut-outs

5CZ = Aircraft Electrical Miscellaneous Stores

5D = Aircraft Armament Electrical Stores

5E = Cable and Wire Electrical Stores

5F = Insulating Materials Electrical Stores

5G = Special Ground Equipment

5H = Standard Wiring System

5J = Batteries Primary and Secondary

5K = Electrical A.G.S and Bonding Stores

5L = Electric Lamps

5P = Ground Charging, Transforming Equipment and Motors

5Q = Ammeters, Micro-ammeters, Milli-ammeters, Voltmeters and Milli-voltmeters

5S = Strip Wiring Components

5UA = Aircraft Engine and Air Driven Electrical Current Producing

Equipment and Spares

5UB = Aircraft Electrically Driven Electrical Current Producing and

Transforming Equipment and Spares

5UC = Aircraft Electrical Current Control Equipment and Spares

5UD = Aircraft Electrical Motors, Blowers and Spares

5UE = Aircraft Electrically Driven Pumps, Accessories and Spares

5V = Aircraft Electrical Domestic Equipment

5W = Aircraft Electrical Actuators, Accessories and Spares

5X = Component Parts of Wiring Assemblies

6 = Nav. & optical Equipt.

6A = Aircraft Instruments

6D = Oxygen Equipment

6F = Aircraft Personnel Equipt.

7; 8, 9 = Aircraft Armaments

9A = Aircraft Towed Target Gear

9B = Armament Ground Instructional Equipment

10A = Miscellaneous Radio (Wireless) Equipment

10AB = Miscellaneous Radio (Radar) Equipment

10AC = Unassembled Items peculiar to Radio with Generic Headings similar

to those in Sections 28 and 29

10AD = Items and Assemblies performing Circuit Functions (Nomenclature

commencing Letters A-K)

10AD = Items and Assemblies performing Circuit Functions (Nomenclature

commencing Letters L-Z)

10AF = Calculating, Indicating and Measuring Equipment

10AG = Tools and Tool Boxes peculiar to Radio

10AH = Telephone Head Equipment, Microphones and Receivers

10AJ = Mountings and their Component Parts

10AK = Dials, Handles, Knobs,Plates, Escutcheon, Pointers, Pressbuttons

and Scales

10AL = Screens and Insulating Components and their Assemblies

10AM = Labels (Radio)

10AP = Boxes, Cases, Covers and Trays, other Cases, Transit

10AQ = Furniture, Tentage, textile Materials and Ventilator Equipment,

peculiar to Radio

10AR = Machinery, Machine and Mechanical Parts other than those in

Section 10AC

(Nomenclature commencing Letters A-K)

10AR = Machinery, Machine and Mechanical Parts other than those in

Section 10AC

(Nomenclature commencing Letters L-Z)

10AT = Windows and Visors

10AU = Strip Metallic

10B = Radio (Wireless and Radar) Aerial and Mast Equipment and

Insulators

10BB = Radio (Radar) Aerial and Mast Equipment and Insulators

10C = radio Chokes, Capacitors and Inductors (see also Joint-Service

Catalogue)

10CV = Joint Service Common Valves

10D = Radio (Wireless and Radar) Equipment, Modulators, Panels,

Receivers, Transmitters etc.

10DB = Radio (Radar) Equipment, panels, Power Units, Racks, Receivers

and Transmitters

10E = Magnets and Radio Valves (Industrial Types)

10F = Radio (Wireless and Radar) Starters and Switch Gear

10FB = Radio (radar) starters and Switch Gear

10G = Ground Telephone and Telegraph Equipment

10GP = Ground Telephone and Telegraph Equipment - Post Office Pattern

10H = Radio Connectors, Discs Indicating, Fuses, Leads, Plugs and

Sockets and Ancillary Parts,

Holders and Terminals.

10HA = Radio (Wireless and Radar) Connectors, Cords Instrument and Leads

10J = Radio Remote Controls

10K = Radio (Wireless and Radar) Power Units and Transformers

10KB = Radio (Radar) Power Units and Transformers

10L = Radio (Wireless and Radar) Control Units

10LB = Radio (Radar) Control Units

10P = Radio (Wireless and Radar) Filter and Receiver Units

10PB = Radio (Radar) Filter and Receiver Units

10Q = Radio (Wireless and Radar) Indicating Units

10QB = Radio (Radar) Indicating Units

10R = Radio (Wireless and Radar) Transmitter Units

10RB = Radio (Radar) Transmitter Units

10S = Radio (Wireless and Radar) Test Equipment

10SB = Radio (Radar) Test Equipment

10T = Radio Monitors and Wavemeters

10U = Radio (Wireless and Radar) Amplifying Units, Loudspeakers and

Sound Reproduction Equipment

10UB = Radio (Radar) Amplifying Units and Loudspeakers

10V = Radio (Wireless and Radar) Oscillator Units

10VB = Radio (Radar) Oscillator Units

10W = Radio Resistors and miscellaneous Spares

10X = Radio Crystal Units

10Y = Cases Transit (general Radio purposes)

11A = Aircraft Bomb Gear

11C = Rocket Projector Gear

12A= Bombs (Live)

12B= Bombs (Dummy)

12C= Ammunition

12E = Torpedoes

12F= Misc. Armament

14 = Photo Equipment

15A = Man-carrying parachute Equip.

15C= Equipt Drop & Sea-Dropping Apparatus

15D = Supply Drop & ASR Equipt.

22C= Flying Clothing

27C= Survival Equipment

40H Gun Turret Cases and Airtight Containers

50A Aircraft Gun Turrets

50CC Boulton Paul Gun Turret and Gun Mounting Tools

50DD Bristol Gun Turret Tools

50EE Frazer Nash Gun Turret Tools

50H Aircraft Gun Turret Maintenance Equipment

50J Free Gun Mountings

26AE Chipmunk T MK 10

26AF Hurricane including Tempest spares

26AJ Spitfire & Seafire

26AL Sunderland 5

26AN Oxford 1 & 2

26AQ Sea Hawk

26AT Wellington B10 T10 & 18

26BA Halifax

26BJ Martinet 1

26BM Attacker F & B

26BN Proctor 3 & 4

26BP Beaufighter TT10

26BT Barracuda 3

26BU Gannet AS1 & T2

26BV Sycamore HR

26BW Dominie 1

26BX Typhoon including Tempest spares

26BY Mosquito & Sea Mosquito

26BZ Firefly

26DA Javelin F (AW)

26DB Whirlwind & Westland Sikorsky S55

26DC Vulcan B

26DD Anson

26DE Victor B1

26DF Beverley C

26DG Seamew

26DH Scimitar F1

26DJ Belvedere HC

26DK Lightening

26DL Comet 2

26DM Britannia

26DN Gnat Trainer

26DP Alouette (British spares)

26DQ Basset CC1

26DR Beaver AL

26DV Venom FB NF & Sea Venom FAW

26EA Lancaster , Lincoln 2 & York C1

26ED Horsa 2

26EH Meteor F8 & T7

26EM Sea Otter

26EN Auster

26ER Tempest 2, TT5 & 6

26ET Meteor NF & TT20

26EV Vickers 1000 Transport Aircraft

26EW Hornet & Sea Hornet

26FA Brigand

26FC Vampire & Sea Vampire

26FH Sea Fury

26FK Hastings

26FL Valetta & Viking

26FM Prentice T1

26FN Devon C or Sea Heron

26FP Shackleton

26FR Winged Targets

26FU Balliol & Sea Balliol

26FV Dragonfly HC & HR

26FW Heron

26FX Hunter & De Havilland N139D(Type 110)

26FY Sea Vixen

26FZ Canberra

26GA Bristol standard parts for Beaufighter, Brigand & Buckmaster

26KK Osprey

26LK Hercules CMK1

26MM SA330E Anglo-French Helicopter

26NA Buccaneer

26NB Belfast

26PH Phantom GRF

26PJ Jet Provost T

26PN Percival Provost T1

26PP Pembroke HC, C1 & Sea Prince

26RA Jaguar

26SA Pioneer CC1

26SH Sea King

26SK Skeeter

26SR Valiant B

26SS Swift

26SW Scout [& Wasp]

26TA Andover

26TD Dominie T

26TP Twin Pioneer

26TT Tiger Moth 2

26TV Varsity T1

26UU Wellington 1

26V Hart DB & India & T

26VA Harrier GR

26VC VC10C

26WA Argosy

26WW Whirlind (helicopter)

26WX Wessex

British hardware

28D Bolts A.G.S.

28E Clips A.G.S.

28F Couplings A.G.S.

28FP Aircraft Fastner and Quick Release Pins

28G Eyebolts A.G.S.

28H Ferrules A.G.S.

28J Filler Caps and Fuel Filters A.G.S.

28K Fork Joints A.G.S.

28L Locknuts, Lockwashers A.G.S.

28M Nuts A.G.S.

28N A.G.S. Miscellaneous A to O

28P Pins A.G.S.

28Q Rivets A.G.S.

28R A.G.S. Miscellaneous P to R

28S Screws A.G.S. Miscellaneous A to O

28T Studs A.G.S.

28U Trunnions and Turnbuckles A.G.S.

28V Unions A.G.S.

28W Washers A.G.S.

28X Wire A.G.S.

28Y A.G.S. Miscellaneous S to Z

29A Bolts and Nuts, General Hardware

29B Screws, General Hardware

29C Eyelets, Roves, Screw Cups, Washers, General Hardware

29E Pins, Woodruff Keys, General Hardware

29F Rivets, General Hardware

Aircraft Reference Numbers

Manufacturer Codes:

AS = Airspeed

AW = Armstrong Whitworth

R3 = Avro

BP = Boulton Paul (possibly EP)

FB = Bristol

DH = DeHaviland

EEP = English Electric Preston

F8 = Fairey Engineering

G5 = Gloster

HA = Hawker – also 41H?

HP = Handley Page

MCO = Morris Cowley Oxford

PAC = Percival Aircraft Corporation

PPA = Miles (Phillips & Powis)

R = Republic

SB = Short Brothers

SFR = Rootes Speke

SR = Saunders Roe

SHB = Short & Harland Belfast

SHR = Short & Harland Rochester

TAY = Taylorcraft

VA = Victory Aircraft

VACB = Vickers Armstrong Castle Bromwich

VACH = Vickers Armstrong Chester

VABL = Vickers Armstrong Blackpool

WA = Westland

Miscellaneous Codes:

AGS = Aircraft General Standard (Often on nuts and bolt heads)

ALCLAD = Aluminium (Or “Alooominum” if from former colonies!)

ALCOA = Aluminium Corporation of America

PSC = Pressed Steel Company

Aircraft Part Codes:

P39 = Airacobra (Bell) AW41 = Albermarle Mk1

652A = Anson (All Mk’s) 660 = Argosy

UC61 = Argus Mk1 (Fairchild) UC61A= Argus Mk II

UC61K= Argus Mk III 701 = Avro Athena T2

540 = Avro 504K 582 = Avro 504N

187 = Baltimore (Martin) 156 = Beaufighter Mk1F

152 = Beaufort 192 = Belvedere (Westland)

B101 = Beverley (Blackburn) C1 555 = Bison

142M = Blenheim Mk IF 149 = Blenheim Mk Ib

160 = Blenheim Mk V 130A = Bombay

B26 = Botha 164 = Brigand

F2A = Bristol Fighter B103 = Buccaneer

B339E = Brewster Buffalo 105A = Bristol Bulldog Mk II & IIa

EA3 = Canberra B2 EA2 = Canberra PR3

EA4 = Canberra Mk24 SC4 = Canberra U/D 10

28 = Catalina Mk I CH47 = Chinook HC1

DHC1 = Chipmunk T10 DH60 = Cirrus Moth Mk I & II

DH106 = Comet Mk I – IV 20 = Commando

C47 = Dakota Mk I C53 = Dakota Mk II

C47A = Dakota Mk III C47B = Dakota Mk IV

P82 = Defiant DH104 = Devon

89A = Dominie Mk I ‘(B = Dominie Mk II

AS10 = Envoy Mk III 229 = Fortress Mk I

60M = Gipsy Moth

HP57 = Halifax Mk I HP59 = Halifax Mk II

HP61 = Halifax Mk III HP63 = Halifax Mk IV

HP63 = Halifax Mk V HP70 = Halifax Mk VIII

HP71 = Halifax Mk IX HP52 = Hampden Mk I

HP54 = Harrow NA16 = Harvard I

NA66 = Harvard II NA88 = Harvard IIa

AT16 = Harvard IIb HP67 = Hastings

HP94 = Hastings C4 DB7 = Havoc I

DB7A = Havoc Mk II P1182 = Hawk (BAe)

C130K = Hercules (Lockheed) HP50 = Heyford

DH103 = Hornet AS51 = Horsa (Also marked AS58)

L-214 = Hudson Mk I L-414 = Hudson Mk II-VI

P1067 = Hunter Mk I P1099 = Hunter Mk6

P1101 = Hunter T7

TypeS = Jaguar TypeM = Jaguar T2

GA5 = Javelin 145 = Jet Provost

683 = Lancaster (All Mks) 691 = Lancastrian

32 = Liberator 22 = Lightning (P-38)

P1B = Lightning Mk IF P25 = Lightning Mk 2F

P26 = Lightning Mk 3F P11 = Lightning T4

P27 = Lightning T5 694 = Lincoln

P8 = Lysander

M14 = Magister Mk I 679 = Manchester

179 = Marauder M25 = Martinet TT1

M9 = Master Mk I M19 = Master Mk II

M27 = Master Mk III M16 = Mentor

G41A = Meteor Mk I G41F = Meteor F4

G43 = Meteor T7 G41K = Meteor F8

G41L = Meteor FR9 G41M = Meteor PR10

NA62B= Mitchell Mk I NA82 = Mitchell II

NA-108= Mitchell III 98 = Mosquito (All Mks)

NA73 = Mustang I (Also NA83) NA91 = Mustang Ia

NA102 = Mustang III NA109 = Mustang IV

NA97 = A-36 Apache (with dive brakes) NA99 = P-51A / Mustang II

NA103 = P-51C (early version) / Mustang III NA104 = P-51B (later version) /

Mustang III

NA111 = P-51C (later version) / Mustang III

NA111 = P-51K-NT (early Dallas-built = Mustang IVA

NA122 = P-51D-NA (later version) / Mustang IV

NA124 = P-51D-NT (late version Dallas built) / Mustang IV

26 = Neptune HS801 = Nimrod (BAe)

AS10 = Oxford MkI & II AS46 = Oxford MkV

P66 = Pembroke F-4 = Phantom

P28 = Proctor I P30 = Proctor II

P34 = Proctor III P31 = Proctor IV

DH82B= Queen Bee (Pilotless?)

C1-13 = Sabre (F-86) 696 = Shackleton

382 = Spiteful 300 = Spitfire Mk I; Ia; Ib

329 = Spitfire Mk IIa & IIb 375 = Spitfire Mk IIc

353 = Spitfire Mk IV 332 = Spitfire Mk Vb

331 = Spitfire Mk Vb 349 = Spitfire Mk Vc & LF Vb

352 = Spitfire F Vb 351 = Spitfire Mk VII

359 = Spitfire Mk III 361 = Spitfire Mk IX

362 & 387 = Spitfire Mk X 365 = Spitfire Mk XI

366 = Spitfire Mk XII & XIII 367 & 353 = Spitfire Mk XIII

369 & 379 = Spitfire Mk XIV & XIVe 380 = Spitfire Mk XVI

394 = Spitfire Mk XVIII 389 & 390 = Spitfire Mk XIX

356 = Spitfire Mk F21; F22 & F24 SB29 = Stirling

S25 = Sunderland 541 = Swift (Shorts)

546 = Swift (Supermarine) 171 = Sycamore HA12

82 = Tiger Moth 81A-1 = Tomahawk Mk I

81A-2 = Tomahawk Mk II 621 = Tutor (Avro)

89 & 93 = Thunderbolt

637 = Valetta 706 & 710 = Valiant

100 = Vampire Mk F1; F3; F5; F9 113 = Vampire NF10

115 = Vampire T11 668 = Varsity

112 = Venom V146 = Ventura

237 = Ventura Mk V HP80 = Victor

498 = Viking C2 FB27 = Vimy Mk IV

698 = Vulcan

236 = Walrus 462 = Warwick ASR Mk I

413 & 611 = Warwick II 460 = Warwick III

474 & 475 = Warwick V 485 = Warwick ASR Mk VI

345 = Washington B1 P14 = Welkin

287 = Wellesley 285 & 290 = Wellington I

408 & 409 = Wellington Ia 415 & 450 = Wellington Ic

298 & 406 = Wellington II 417 & 440 = Wellington III

410 & 424 = Wellington IV 407 & 421 = Wellington V

442 & 449 = Wellington VI 429 = Wellington VIII

440 = Wellington X 454 & 458 = Wellington XI

455 = Wellington XII 466 = Wellington XIII

467 = Wellington XIV P9 = Whirlwind

188 & 38 = Whitley Mk I 197 = Whitley II

205 = Whitley III 209 & 210 = Whitley IV & IVa

207 = Whitley V 217 = Whitley VII

244 = Wildebeeste I 258 = Wildebeeste II

267 = Wildebeeste III 286 = Wildebeeste IV

685 = York C1

Air Ministry Equipment Codes:

No. 5 = Electrical Equipment No.6 = Nav. & optical Equipt.

No.6A = Aircraft Instruments

No.6D = Oxygen Equipment No.6F = Aircraft Personnel Equipt.

No. 7; 8; 9 = Aircraft Armaments No.10 = Comms. Equipt.

No.11 = Bombing Gear No.12A= Bombs (Live)

No.12B= Bombs (Dummy) No.12C= Ammunition

No.12E = Torpedoes No. 12F= Misc. Armament

No.14 = Photo Equipment No.15A = Man-carrying parachute Equip.

No. 15C= Equipt Drop & Sea-Dropping Apparatus No.15D = Supply Drop & ASR Equipt.

No. 22C= Flying Clothing No.27C= Survival Equipment

6A Aircraft Engine and Flying Instruments, Accessories and Spares

6B Aircraft Navigation Equipment, Accessories and Spares

6C Instrument Test Equipment, Tools, Accessories and Unit Equipment Spares

6D Aircraft Gaseous Apparatus and Ancillary Equipment

6E Miscellaneous Instruments, Accessories and Unit Servicing Spares

6H Aircraft Automatic Pilots, Marks 4 and 8, Major Components, Servicing Spares

and Tools

6J Aircraft Automatic Pilots, Types A3 and A3A and A.L.1, Major Components,

Servicing Spares and Tools

6S Automatic Stabilisers, Major Components, Servicing Spares and Tools

6T Aircraft Automatic Pilots, Marks 9, 10, 10A, 13, SEP 2, 14 and 17, Major

Components, Servicing Spares and Tools

6W Instrumemnt Ancillaries to Radio Equipment

6Z Radio activity Detection Equipment and Accessories, Unit and Major Servicing

Spares

13 Drawing Instruments

52 Recognition Models

54A Plotting Equipment

5A Ground Lighting and Miscellaneous Equipment

5B Aircraft Wiring Assemblies

5CW Aircraft Electrical Switches, Switchboxes, Relays and Accessory Items

5CX Aircraft Electrical Lamps, Indicators, Lampholders and Accessory Items

5CY Aircraft Electrical Plugs, Sockets, Circuit Markers, Suppressors and

Accumulator Cut-outs

5CZ Aircraft Electrical Miscellaneous Stores

5D Aircraft Armament Electrical Stores

5E Cable and Wire Electrical Stores

5F Insulating Materials Electrical Stores

5G Special Ground Equipment

5H Standard Wiring System

5J Batteries Primary and Secondary

5K Electrical A.G.S and Bonding Stores

5L Electric Lamps

5P Ground Charging, Transforming Equipment and Motors

5Q Ammeters, Micro-ammeters, Milli-ammeters, Voltmeters and Milli-voltmeters

5S Strip Wiring Components

5UA Aircraft Engine and Air Driven Electrical Current Producing Equipment and

Spares

5UB Aircraft Electrically Driven Electrical Current Producing and Transforming

Equipment and Spares

5UC Aircraft Electrical Current Control Equipment and Spares

5UD Aircraft Electrical Motors, Blowers and Spares

5UE Aircraft Electrically Driven Pumps, Accessories and Spares

5V Aircraft Electrical Domestic Equipment

5W Aircraft Electrical Actuators, Accessories and Spares

5X Component Parts of Wiring Assemblies

10A Miscellaneous Radio (Wireless) Equipment

10AB Miscellaneous Radio (Radar) Equipment

10AC Unassembled Items peculiar to Radio with Generic Headings similar to those

in Sections 28 and 29

10AD Items and Assemblies performing Circuit Functions (Nomenclature commencing

Letters A-K)

10AD Items and Assemblies performing Circuit Functions (Nomenclature commencing

Letters L-Z)

10AF Calculating, Indicating and Measuring Equipment

10AG Tools and Tool Boxes peculiar to Radio

10AH Telephone Head Equipment, Microphones and Receivers

10AJ Mountings and their Component Parts

10AK Dials, Handles, Knobs,Plates, Escutcheon, Pointers, Pressbuttons and Scales

10AL Screens and Insulating Components and their Assemblies

10AM Labels (Radio)

10AP Boxes, Cases, Covers and Trays, other Cases, Transit

10AQ Furniture, Tentage, textile Materials and Ventilator Equipment, peculiar to

Radio

10AR Machinery, Machine and Mechanical Parts other than those in Section 10AC

(Nomenclature commencing Letters A-K)

10AR Machinery, Machine and Mechanical Parts other than those in Section 10AC

(Nomenclature commencing Letters L-Z)

10AT Windows and Visors

10AU Strip Metallic

10B Radio (Wireless and Radar) Aerial and Mast Equipment and Insulators

10BB Radio (Radar) Aerial and Mast Equipment and Insulators

10C radio Chokes, Capacitors and Inductors (see also Joint-Service Catalogue)

10CV Joint Service Common Valves

10D Radio (Wireless and Radar) Equipment, Modulators, Panels, Receivers,

Transmitters etc.

10DB Radio (Radar) Equipment, panels, Power Units, Racks, Receivers and

Transmitters

10E Magnets and Radio Valves (Industrial Types)

10F Radio (Wireless and Radar) Starters and Switch Gear

10FB Radio (radar) starters and Switch Gear

10G Ground Telephone and Telegraph Equipment

10GP Ground Telephone and Telegraph Equipment - Post Office Pattern

10H Radio Connectors, Discs Indicating, Fuses, Leads, Plugs and Sockets and

Ancillary Parts,

Holders and Terminals.

10HA Radio (Wireless and Radar) Connectors, Cords Instrument and Leads

10J Radio Remote Controls

10K Radio (Wireless and Radar) Power Units and Transformers

10KB Radio (Radar) Power Units and Transformers

10L Radio (Wireless and Radar) Control Units

10LB Radio (Radar) Control Units

10P Radio (Wireless and Radar) Filter and Receiver Units

10PB Radio (Radar) Filter and Receiver Units

10Q Radio (Wireless and Radar) Indicating Units

10QB Radio (Radar) Indicating Units

10R Radio (Wireless and Radar) Transmitter Units

10RB Radio (Radar) Transmitter Units

10S Radio (Wireless and Radar) Test Equipment

10SB Radio (Radar) Test Equipment

10T Radio Monitors and Wavemeters

10U Radio (Wireless and Radar) Amplifying Units, Loudspeakers and Sound

Reproduction Equipment

10UB Radio (Radar) Amplifying Units and Loudspeakers

10V Radio (Wireless and Radar) Oscillator Units

10VB Radio (Radar) Oscillator Units

10W Radio Resistors and miscellaneous Spares

10X Radio Crystal Units

10Y Cases Transit (general Radio purposes)

9 Bomb and Torpedo Sights

9A Aircraft Towed Target Gear

9B Armament Ground Instructional Equipment

11A Aircraft Bomb Gear

11C Rocket Projector Gear

40H Gun Turret Cases and Airtight Containers

50A Aircraft Gun Turrets

50CC Boulton Paul Gun Turret and Gun Mounting Tools

50DD Bristol Gun Turret Tools

50EE Frazer Nash Gun Turret Tools

50H Aircraft Gun Turret Maintenance Equipment

50J Free Gun Mountings

14A Cameras

14B Photographic Processing Equipment, Enlargers and Accessories

14C Projection, Assessing Apparatus and Epidiascopes

14H Photographic Test Apparatus

6F Aircraft Personnel Equipment

15A Man-carrying Parachutes

15C Equipment-dropping and Sea-rescue Apparatus

15D Air Sea Rescue and Equipment, and Supply-dropping Parachutes

25A Propellors

25B Aircraft Radiators

25D Spinners for Fixed Pitch Propellers and Fairey Spares for Metal Propellers

27A Aircraft Wheel Equipment

27B Aircraft Air and Oil Filters, Fuel and Oil Coolers

27D Miscrellaneous Aircraft Cover Equipment

27F Aircraft Pumps and fuelling Equipment (Airborne)

27G Aircraft Brake System Equipment

27H Miscellaneous Aircraft Equipment

27J Aircraft Control Handles with Gun, Camera, R.P. and Brake Operating

Mechanisms

27K Teleflex Aircraft Remote Control Equipment

27KA Exactor Aircraft Remote Control Equipment

27KB Aircraft Controls - Roller Chains

27KD Pressurised Cabin Equipment - Normalair

27M Aircraft Hydraulic and Undercarriage Equipment - Lockheed

27N Airborne Fire Fighting Equipment

27R B.L.G. Oleo Leg Equipment

27S Standard Ball and Roller Bearings other than M.T.

27T Controllable Gills

27U Airborne Heaters

27UA Aircraft Cabin Cooling Equipment

27V Aircraft Controls - Teddington

27VA Aircraft Controls - Dunlop

27VC Aircraft Controls - Palmers

27W Aircraft Hydraulic and Undercarriage Equipment, Standard Design

27WW Aircraft Windscreen Wiper Equipment

27Z Turner Duplex Hand Pumps for Aircraft Hydraulic Systems

27ZA Exactor Self Sealing Couplings

28D Bolts A.G.S.

28E Clips A.G.S.

28F Couplings A.G.S.

28FP Aircraft Fastner and Quick Release Pins

28G Eyebolts A.G.S.

28H Ferrules A.G.S.

28J Filler Caps and Fuel Filters A.G.S.

28K Fork Joints A.G.S.

28L Locknuts, Lockwashers A.G.S.

28M Nuts A.G.S.

28N A.G.S. Miscellaneous A to O

28P Pins A.G.S.

28Q Rivets A.G.S.

28R A.G.S. Miscellaneous P to R

28S Screws A.G.S. Miscellaneous A to O

28T Studs A.G.S.

28U Trunnions and Turnbuckles A.G.S.

28V Unions A.G.S.

28W Washers A.G.S.

28X Wire A.G.S.

28Y A.G.S. Miscellaneous S to Z

29A Bolts and Nuts, General Hardware

29B Screws, General Hardware

29C Eyelets, Roves, Screw Cups, Washers, General Hardware

29E Pins, Woodruff Keys, General Hardware

29F Rivets, General Hardware

4A Workshop Equipment

4C Airfield Equipment

4F Air Compressors and Servicing Trolleys

4G Aircraft Servicing and Ground handling Equipment

4K General Ground Equipment (including Refuelling Equipment)

4N Sparking Plug Testing and Servicing Equipment

4FZ Air Compressor Spares

71B Plants (Mobile, Transportable and Static) and Plant Accessories

__________________

The

voltage of an instrument can be a good way to identify what type of

aircraft it was used in, as a rule 12 volt was used in fighters and

single engine aircraft and 24 volt was used in Bombers or multi engine

aircraft of coarse there always are exceptions to this rule but in

general its a good start.

Voltage information supplied

by Spitfire Spares member Dave. Instrument voltage is generally marked on the

case and this info will be invaluable when identifying instrument use.

Spitfire IX - 12v

Spitfire XXII - 12V

Spitfire 14 - 12V

Spitfire 16 - 12V

Spitfire 19 - 12V

Spitfire 22 & 24 - 24V

Wellington - 24V

Beaufighter - 24V

Lincoln - 24V

York - 24V

Dakota I -12V

Dakota III - 24V

Anson I - 12v

Anson 22 - 24V

Lancaster - 24V

Stirling - 24V

Halifax -24V

Varsity - 24V

Sea Fury - 24V

Tempest II -24V

Meteor III - 24V

Mosquito - 24V

Vampire - 24V

Harvard - 12v

Oxford - 12v

Hornet - 24v

Canberra - 24v

Chipmunk - 24V

Mustang - 24v

Hurricane - 12V

Spitfire instrument panels

by Herbert Puuka

Differences between

the Mk versions of Merlin-powered Spitfires:

Mk I

Early oxygen regulator

hole for landing light

Gunsight and generator

switch

One starter button

Fuel pressure gauge or

warning lamp with adapter plate

Round temperature

gauges

One or two round fuel

gauges

Mk II

Early oxygen regulator

hole for landing light

Gunsight and generator switch

One starter button

Fuel pressure gauge or

warning lamp with adapter plate

Round temperature

gauges

Round fuel gauge

Hole for cardridge

starter handle

Mk V

Early oxygen regulator

With or without hole

for landing light

Gunsight switch

Two starter buttons

Fuel pressure gauge or

lamp

Round temperature

gauges

Round fuel gauge

Mk IX

Early or late oxygen

regulator

Two starter buttons

Supercharger panel

Fuel pressure warning

lamp

Round or rectangle

temperature gauges

Round or rectangle

fuel gauges

Conclusion:

After some time of

research and collecting cockpit pictures I discovered, that the Mk V panels

introduced the boost coil switch

and the hole for the

cartridge starter handle disappeared. Together with the two-speed supercharger

engines appeared the

supercharger panel

of the Mk. IX and later Mks. The generator switch disappeared with Mk V, the

gunsight switch with

Mk IX. I seem to have

no picture of a metal panel so the change to Paxoline panels took place very

early.

List of instruments Spitfire Mk

XIV

Dunlop air pressure gauge AHO 4040

Tail trimming indicator 30034

Master switch 5C/1974

Ignition switch box 5C/548

Tail wheel warning lamp 35136 flange plate 5C/1553 or 5C/1069

Dimmer switches 5C/367

Time of flight clock 6A/579 or 6A/1150 or 6A/1002

Undercarriage indicator 30036 5C/1731

Oxygen regulator 6D/513 or 6D/695

Flap control valve 34959

Terminal block 5C/430

Gunsight dimmer switch 5C/763

Gunsight socket 5C/892

Voltmeter 5A/1636

Engine speed indicator 6A/450 or 6A/1191

Dunlop pipe connection AHO 2790

Supercharger switch 10H/11714

Supercharger warning lamp 5C/1553 or 5C/1069

Boost gauge 6A/1427 or 6A/1581

Oil pressure gauge 6A/536

Oil thermometer 6A/1094 or 6A/1340

Radiator thermometer 6A/1100 or 6A/1480

Fuel pressure warning lamp 35136 flange plate 5C/1553 or 5C/1069

Fuel content warning lamp 35136 flange plate 5C/1553 or 5C/1069

Fuel content gauge 6A/1569 727 FG

Starter switch 5C/540 or 5C/898

Starter switch flap cover 36134 or 5C/1267

Compass deviation card holders 6A/387

BFP:

Air Speed indicator 6A/587

Artificial horizon 6A/589 or 6A/1488 or 6A/711

Rate of climb meter 6A/942

Altimeter 6A/577 or 6A/685 or 6A/1203

Direction indicator 6A/602 or 6A/1209

Turning indicator 6A/675

Control Grip info by Herbert Puukka

A.P.1086, Part 11E lists the following "ring control handles"

for the Spitfire:

AH2174 for Spitfire IA, IIA, VA

AH8068 for Seafire, Spitfire IB, IIB, VB, VC, F.VI, VII, VIII, FIX, FXII, FXXI

AH2174

Spitfire IA,

IIA, VA

AH8068

Seafire,

Spitfire IB, IIB, VB, VC, FVI, VII, VIII, FIX, FXII, FXXI

AH2040

with brake

lever: Hurricane, Battle, Fulmar, Lysander I and II, Skua, Swordfish and

Whirlwind.

AH2242

Harvard I and

II

AH8272

Firefly, Firebrand and Sea Hornet

The AH References are Dunlop's own and they are usually to be found stamped onto

the lower portion of the grip. The first listed one is for the classic round,

pneumatic gun firing button, the latter is for the selective twin pneumatic

switch.

If it is Spitfire it will have a brake lever on the back. No lever or mounting

pin then again most probably a Canadian Harvard that had toe brakes.

Hurricane grips should have the pipe work external to the grip, i.e. it doesn't

go through the hole in the top of the control column.

A proper grip for the Harvard I and II should be stamped AH2242, a proper

Hurricane, AH2040.

For the record, AH2040 also "fits" the Battle, Fulmar, Lysander I and II, Skua,

Swordfish and Whirlwind

Instrument info by Herbert Puukka

MK XIV Spitfire Instrument list.

Dunlop air pressure

gauge AHO 4040

Tail trimming

indicator Supermarine 30034

Master

switch 5C/1974

Ignition switch box

5C/548

Tail wheel warning

lamp 35136 flange plate 5C/1553 or 5C/1069

Dimmer

switches 5C/367

Time of flight

clock 6A/579 or 6A/1150 or

6A/1002

Undercarriage

indicator Supermarine 30036 5C/1731

Oxygen

regulator 6D/513 or 6D/695

Flap control

valve 34959

Terminal block

5C/430

Gunsight dimmer

switch 5C/763

Gunsight

socket 5C/892

Voltmeter 5A/1636

Engine speed

indicator 6A/450 or 6A/1191

Dunlop pipe

connection AHO 2790

Supercharger

switch 10H/11714

Supercharger warning

lamp 5C/1553 or 5C/1069

Boost

gauge 6A/1427 or 6A/1581

Oil pressure

gauge 6A/536

Oil

thermometer 6A/1094 or 6A/1340

Radiator

thermometer 6A/1100 or 6A/1480

Fuel pressure warning

lamp 35136 flange plate 5C/1553 or 5C/1069

Fuel content warning

lamp 35136 flange plate 5C/1553 or 5C/1069

Fuel

content gauge 6A/1569

727 FG

Starter

switch 5C/540 or 5C/898

Starter switch flap

cover 36134 or 5C/1267

Compass deviation card

holders 6A/387

BFP:

Air Speed

indicator 6A/587

Artificial

horizon 6A/599 or 6A/1488 or 6A/711

Rate of climb

meter 6A/942

Altimeter 6A/577 or 6A/685 or

6A/1203

Direction

indicator 6A/602 or 6A/1209

Turning indicator

6A/675

Instrument

List Mk1 to MKIX Spitfire

Dunlop

air pressure gauge AHO 4040

Tail trimming

indicator 30034

Ignition switch

box 5C/548

Dimmer

switches 5C/367

Time of flight

clock 6A/579 or 6A/1150 or

6A/1002

Undercarriage

indicator 30036 5C/1731

Oxygen

regulator 6D/513 or 6D/695

Switchbox 5C/543

Flap control

valve 34959

Gunsight dimmer

switch 5C/763

Gunsight

socket 5C/892

Voltmeter

5A/1636

Engine speed

indicator 6A/450

Supercharger

switch 10H/11714

Supercharger warning

lamp 5C/1553 or 5C/1069

Boost

gauge 6A/789

Fuel pressure

gauge 6A/512

Oil pressure

gauge 6A/556

Oil

thermometer 6A/155

Radiator

thermometer 6A/494

Fuel pressure warning

lamp 35136 flange plate 5C/1553 or 5C/1069

Fuel content

gauge 6A/703

Fuel gauge pushbutton

switch 6A/646

Starter

switch 5C/540

Starter switch flap

cover 32936

Compass deviation card

holders 6A/387

BFP:

Air Speed

indicator 6A/563 or 6A/587

Artificial

horizon 6A/599 or 6A/1488 or 6A/711

Rate of climb

meter 6A/723 or 6A/942

Altimeter 6A/577 or 6A/685 or

6A/1203

Direction

indicator 6A/602 or 6A/1209

Turning indicator

6A/675

Mk II Hurricane

instrument list

Engine

starter pushbutton 5C/898

Booster coil

pushbutton 5C/898

Boost control

cut-out

Time of flight

clock 6A/581

Oxygen

regulator Mk VIII

(6D/513)

Undercarriage

indicator switchbox 5C/1991

Undercarriage

indicator 5C/4845

Compass

deviation card holders 6A/387

Instrument

flying panel 6A/616

Engine speed

indicator 6A/450

Reflector sight

switchbox 5C/543

Boost

gauge 6A/486 or

6A/699 or 6A/789

Fuel contents

gauge selector switch 6A/1113

Fuel contents

gauge (28 and 33 gallons) 6A/792 or 6A/812 or 6A/813

Fuel pressure

gauge/warning light 6A/512 or 5C/1553 or 5C/1069

Oil

thermometer 6A/155

Radiator

temperature gauge 6A/494

Oil pressure

gauge 6A/311

3-Switchbox

5C/544

Ignition

switchbox 5C/548

Magneto

switchbox (only MK I) 5C/547

BFP:

Air Speed

indicator 6A/583 or 6A/1293

Artificial

horizon 6A/599 or

6A/711

Rate of climb

meter 6A/723 or 6A/942

Altimeter

6A/577 or 6A/685

Direction

indicator 6A/602

Turning

indicator 6A/675

Thanks to

Herbert for this valuable info that must have taken many hours to research